New Covid-19 variants are coming to light. These are each a version of the virus that has undergone genetic changes, also known as mutations.

Some mutations may change the characteristics of the virus and how it interacts with humans – for example, how quickly it spreads.

Here’s what we know about them.

The UK variant

The first is the UK variant, which has been called the Variant of Concern 202012/01 (VOC) by Public Health England. It is sometimes referred to as B.1.1.7. This variant is believed to be more infectious – and, as Boris Johnson revealed in a press briefing on January 22 – it is now thought it could be more deadly, too.

The South Africa variant

A second, “highly concerning” variant is the South Africa variant (also known as 501Y.V2), which has also been detected in the UK, in two cases in December. A recent rise in cases in South Africa appears to be a result of 501Y.V2, which is said to carry a heavier viral load and seems to be more prevalent among young people.

The Brazil variant

The third variant has been referred to as the Brazil variant – although there are actually two Brazilian variants on scientists’ radars right now. One of them is considered to be “of concern” and is not thought to have reached the UK. The other, which is thought to be less of a problem, has been circulating in the UK since summer 2020.

How has the virus changed?

There are eight key strains – or clades – of the virus that have been identified worldwide. Think of them as branches on a tree. They all stem from one common ancestor, but have branched off (mutated) to become different things.

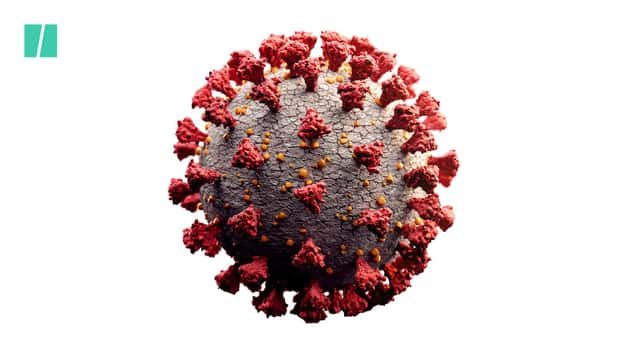

The new UK variant is defined by the presence of specific mutations, rather than a clade, Public Health England told HuffPost UK. This particular variant includes a mutation in the “spike” protein, which may result in the virus spreading more easily between people.

It’s not unusual for a virus to mutate. In fact, there are around one to two mutations of SARS-CoV-2 per month, which means many thousands of mutations have developed since the virus emerged in 2019, according to the Covid-19 Genomics UK Consortium.

How serious are these new variants?

The UK variant that first developed in late summer or early autumn 2020 is far more transmissible than previous versions, according to a study from Imperial College London that is still preprint (ie. research shared before it has been peer reviewed).

The report on the new variant suggests it increases the R number by between 0.4 and 0.7. It also found “a small but statistically significant shift” towards under 20s being more affected by the new variant.

Boris Johnson said on January 22: “In addition to spreading more quickly, it also now appears that there is some evidence that the new variant, the variant that was first identified in London and the south-east, may be associated with a higher degree of mortality.”

Chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance explained that with the original strain of Covid-19, roughly 10 out of every 1,000 men in their 60s who get infected would be expected to die. With the new variant, this risk would rise to roughly 13 or 14 out of every 1,000.

Vallance stressed the data was “currently uncertain”, but conceded “obviously this is a concern”.

The South African variant is also thought to be more transmissible. Speaking to BBC radio on January 4, Matt Hancock said he was “incredibly worried” about the South African variant and said it was “even more of a problem than the UK new variant” as it is thought to be more transmissible and has mutated further.

There is concern that the Brazil variant is also more transmissible. During a briefing, Prof Barclay said initial studies suggest the Brazil variants “might impact the way that some people’s antibodies can see the virus” – this means there may be more of a risk of reinfection.

But further research is needed to determine whether this is the case.

Do the variants cause different symptoms?

There is some evidence emerging that the UK variant might have different symptoms to what we’re used to.

Coughs, sore throats, fatigue and muscle pain are more commonly reported symptoms of the new UK coronavirus variant, according to data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). However, fewer people testing positive for the variant appear to be experiencing a loss of taste or smell.

People are still advised to keep an eye out for a fever, persistent cough and a change to, or loss of, smell or taste – and to book a test if they experience any of these symptoms.

Dr Susan Hopkins, Test and Trace and PHE joint medical advisor, reminds people that the best way to stop infection is to stick to the rules: “wash our hands, wear a face covering and keep our distance from others.”

Does the vaccine still work with these variants?

Scientists are monitoring how the virus is mutating because it could impact the effectiveness of vaccines, the severity of illness, the transmissibility of the virus (how easily it spreads) and also the effectiveness of treatments, such as antiviral drugs.

The Oxford/AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine is “just as effective at fighting the UK variant as it is the original virus”, new research suggests. Oxford University researchers who developed the vaccine say it has a similar efficacy against the variant first detected in Kent and the South East of the UK, compared to the original strain of Covid-19 that it was tested against.

Andrew Pollard, chief investigator on the Oxford vaccine trial, said: “Data from our trials of the ChAdOx1 vaccine in the United Kingdom indicate that the vaccine not only protects against the original pandemic virus, but also protects against the novel variant, B117, which caused the surge in disease from the end of 2020 across the UK.”

Professor Tom Solomon, director of the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections at the University of Liverpool, previously said: “Just because there has been a small change in the virus’ genetic make-up, this does not mean it is any more virulent, nor that vaccines won’t be effective.

“Our experience from previous similar viruses suggests that the vaccines will be effective despite small genetic changes.”

However, Sir Patrick Vallance said a press briefing on January 22 that the Brazilian and South African variants are of more concern than the UK strain because there are fears they may be less susceptible to vaccines.

The chief scientific adviser told the Downing Street press conference: “We know less about how much more transmissible they are. We are more concerned that they have certain features that they might be less susceptible to vaccines.

“They are definitely of more concern than the one in the UK at the moment, and we need to keep looking at it and studying it very carefully.”

One preprint study found the vaccine did appear to work against the spike protein behind both the strains from the UK and South Africa. Professor Lawrence Young, a virologist at the University of Warwick, said this was “encouraging news”.

“The preprint demonstrates that antibodies from individuals vaccinated with the Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA vaccine is able to block infection (neutralise) with an engineered form of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that contains one of the key mutations in the spike gene (N501Y) found in the UK variant,” he said.

“This mutation is also present in the South African variant. However, for both virus variants there are other changes which might affect infectivity and these have not been examined.”

Professor Stephen Evans, an expert in pharmacoepidemiology from London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said that while this finding was “good news”, it did not yet give total confidence that the Pfizer (or other) vaccines would definitely give protection against the variants.

“We need to test this in clinical experience and the data on this should be available in the UK within the next few weeks,” he said.

Dr Richard Lessells, an infectious disease expert in South Africa, previously told the Guardian: “There are a few more concerns with our variant [than that in the UK] for the vaccine … But we are now doing the careful, methodical work in the lab to answer all the questions we have, and that takes time.”

In the UK, Sir John Bell, regius professor of medicine at Oxford University, who helped develop its vaccine, also aired concerns over the South African variant, as it has undergone “substantial changes in the structure of the [virus] protein”.

He told Times Radio: “My gut feeling is the vaccine will be still effective against the Kent [ie. UK] strain. I don’t know about the South African strain – there’s a big question mark about that.”

Dr Zania Stamataki, a viral immunologist at the University of Birmingham, previously said that if the Covid-19 vaccines do need to be amended, “it will not be a major undertaking to update the new vaccines when necessary in the future.

“This year has seen significant advances take place to build the infrastructure for us to keep up with this coronavirus,” she said.

The vaccine from US company Novavax has been shown to be 89% effective in preventing Covid-19 and preliminary analysis has shown it to be nearly as effective in protecting against the UK variant, and about 60% against the South African strain. The UK has secured 60 million doses of the jab.