Nowadays, you wouldn’t bat an eyelid at putting on a seatbelt for your own safety when sitting in your car – or anyone else’s. Yet right up to the 1980s, seatbelt uptake was pretty low until laws changed to make them mandatory.

Fast forward to pandemic times and we’ve witnessed a similar trajectory on mask-wearing. For so many, it’s become second nature to whip a face cover from their bag or pocket before entering a shop or hopping on the bus.

But in the first half of 2020, it was touch and go as to whether western nations would even get on board with the idea.

It all started with a bunch of experts who, when the pandemic first hit, fought hard for officials to recognise mask-wearing as a form of protection from the virus. In March 2020, a group of researchers and scientists started the global #Masks4All movement, led by Australian research scientist Jeremy Howard. They cited evidence that even cloth masks limited the spread of Covid-19 at a time when personal protective equipment (PPE) like surgical and N95 masks was in dangerously short supply.

Around the same time, pockets of people in the UK were starting to cotton on to the fact that masks, even homemade ones, were better than nothing – but most of us remained staunchly against the idea. Some who adopted mask-wearing before it was recommended by officials found themselves on the receiving end of harsh glares and even abuse.

Deborah Stevens, 60, a supermarket worker at Tesco in Royston, Hertfordshire, would turn up to work in a mask to try and protect herself and her family, particularly her daughter who needed to shield for medical reasons.

She recalls stares from customers. They made her feel as though she was doing “something that wasn’t really needed,” she told HuffPost UK earlier this year. “And I had to do that for myself and for my family, that was the only way I could cope, to protect myself the best I possibly could.”

Trisha Greenhalgh, professor of primary health care services at the University of Oxford, was one of the key mask influencers in the UK, pushing for people to wear homemade face covers from very early on. She could often be found tweeting advice on how to make cloth coverings from t-shirts and singing the praises of using pantyliners as mask filters.

On April 24, 2020 – a month into England’s first lockdown – Prof Greenhalgh told HuffPost UK that wearing face masks was “a socially responsible thing to do and may save lives”. A year on, she stands by that message.

She remembers the incident that made her realise mask-wearing could be hugely beneficial: a performance of Bach’s St John Passion in Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw auditorium on March 8 that led to 102 of 130 choir members developing symptoms of Covid-19. Sadly, four people linked to the choir died.

“This massive super-spreader event simply cannot be explained by ‘fomites’ [things people touch in common] or droplets [which fall with gravity],” she says. “The virus had to be airborne. So we had to stop it getting into the air.”

Getting others – especially doctors – on board with the idea of mask-wearing as a protective measure for the public was a huge challenge, she tells HuffPost UK. “They had a mindset that we should exercise extreme caution when introducing new interventions, hence masks should not be recommended until we had incontrovertible proof of their efficacy and safety.

“But compared to a new drug or vaccine, the risk of serious harm from face masks is extremely low, and the potential for benefit at population level could be high. It was abundantly clear to me that the well-rehearsed reasons for advocating caution in clinical trial research did not hold here.”

Prof Greenhalgh and colleagues published a paper on April 9, 2020 arguing just that. There’s since been plenty of evidence to suggest face masks work not only in protecting others but also – to some degree – the wearer. But while other countries rushed to adopt mask-wearing, there was a lot of flip-flopping from government officials in the UK who couldn’t seem to decide whether they should recommend that we wear masks or not.

The lack of consistent messaging led to confusion, which ultimately helped contribute to anti-mask sentiment, psychologists have said since.

Way back in January, a blog post from Public Health England said there was “very little evidence of widespread benefit” to wearing a face mask outside clinical settings such as hospitals. In March, England’s deputy chief medical officer Dr Jenny Harries said of masks: “For the average member of the public wandering down the street, it is really not a good idea.” And later, on April 24, health secretary Matt Hancock said the evidence on the effectiveness of face masks was “weak” and there were no plans to make them mandatory.

Of course, the government was facing huge shortages in PPE, but there was precious little suggestion that homemade face covers were a viable option.

Four days later came a momentous shift in discourse: Scotland became the first UK nation to officially recommend the use of face coverings in public places and just two days after that, prime minister Boris Johnson suggested face coverings were “useful” to guard against coronavirus and could give people the confidence to head back to work.

But another whole month passed before mask wearing became mandatory on English public transport in June and then in indoor public settings in July, with fines for anyone who didn’t abide by the rules (and wasn’t exempt from wearing a mask for physical or mental health reasons).

Prior to this, thousands were still catching public transport to work, packed in like sardines (despite the stay at home message, many simply had no choice but to go to work), and public transport workers were dying at high rates. Studies have since shown London bus drivers were three times more likely to die from the virus than other workers.

A YouGov poll from June 2020 suggests more people were not wearing masks than were: less than a quarter (21%) of Brits wore a mask or cover when out in public. People in France, Spain, Italy and Germany had widely adopted masks at this point, but the UK lagged far behind. Only in Scandinavia and Australia were people less likely to wear masks.

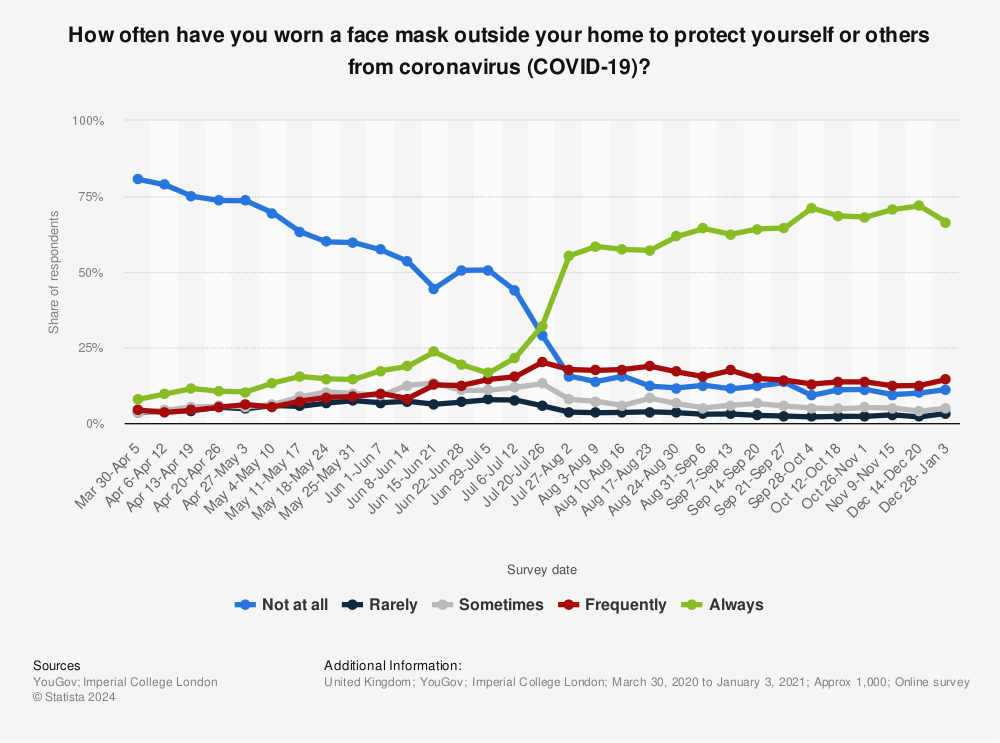

But when mask-wearing was made mandatory in shops and other indoor public spaces, people began to sit up and take notice. Survey results showed the tipping point when most Brits went from never wearing masks to always wearing them when out and about, came when they were made mandatory.

All of a sudden, you were more likely to get glared at if you weren’t wearing a mask in the supermarket. Much like the change in seatbelt laws before it, Brits went from mask-avoidant to aficionados in the space of weeks.

Prof Greenhalgh says she dearly wishes the change of policy had come earlier and been more decisive. “If UK policy had changed in April instead of July, for example, so many thousands more lives could have been saved,” she says.

Now, as lockdown eases, the conversation is turning to masks again – but this time, the question is how much longer we’ll be required to wear them.

The UK government has confirmed that from May 17, pupils in England will no longer have to wear face coverings in schools and colleges, where Covid-19 transmission remains low, while health secretary Matt Hancock suggested mandatory mask-wearing might change for everyone else from June 21.

However, there is no consensus. With children and most young people not yet vaccinated, many experts say there’s “no reason” to expect the virus will hold back if measures like wearing masks are removed. Scientists on the government’s Sage committee reportedly told ministers that pupils should continue to wear face masks into the summer.

Could this be yet another mask mistake? There are concerns over the long-term consequences of the virus in children – or long Covid – and we know kids aren’t immune from experiencing debilitating symptoms, although more research is needed in this area.

The next big push from scientists is urging the importance of indoor ventilation, particularly in public spaces and businesses. Writing in the BMJ, a group of respiratory experts suggested that if we want to stop the spread of Covid-19, we should focus on tackling airborne transmission.

The conversation is shifting from masks to air and just this week, another group of 39 researchers from 14 countries argued we spend most of our time indoors, but the air we breathe inside buildings is not regulated to the same degree as the food we eat and the water we drink – and this, they say, needs to change.

“Air can contain viruses just as water and surfaces do,” said Shelly Miller, professor of mechanical and environmental engineering at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “We need to understand that it’s a problem and that we need to have, in our toolkit, approaches to mitigating risk and reducing the possible exposures that could happen from build-up of viruses in indoor air.”

This call to action comes less than two weeks after the World Health Organisation (WHO) updated its website to acknowledge that SARS-CoV-2 is spread predominantly through the air – and 10 months after it acknowledged the potential for aerosol transmission. Governing bodies need to extend indoor air quality guidelines to include airborne pathogens, researchers said – and to recognise the need to control airborne transmission of respiratory infections.

Especially if we want masks to become a thing of the past.

“Let’s now not waste time until the next pandemic,” said Jose-Luis Jimenez, a professor of chemistry at the University of Colorado. “We need a societal effort. When we design a building, we shouldn’t just put in the minimum amount of ventilation that’s possible, but instead we should keep ongoing respiratory diseases, such as the flu, and future pandemics in mind.”

“Air in buildings is shared air,” added Prof Miller. “It’s not a private good, it’s a public good. And we need to start treating it like that.”