We are both journalists, by training. We are both mental health campaigners.

One of us, in particular, after jumping the fence to politics, has had a lot to say about journalists and journalism over the years, not all good.

The other has spent years in journalism safety, knowing this is more than the elimination of physical risk. But today both of us are worried, for journalists.

We are talking mental health. And asking, whether media owners and editors are taking sufficient account of the mental health implications for their journalists in the current environment.

Politicians targeting the media as enemies, even while claiming to support free speech. Technological change leading to the need for ever more output prepared and produced by, all too often, ever fewer people. Fake news. Never-ending breaking news. Harassment and abuse, especially online, especially of women.

Add to this the huge financial uncertainty of the media, all too often chronic job insecurity, with the pandemic thrown in, and you have something of a cocktail for mental ill health.

“Journalism at its best is about the pursuit of truth. Owners and editors need to face up to the truth that right now, a lot of people are pretending to cope when they aren't”

Most journalists thrive under pressure. Hence their gravitation to an industry which rewards risk taking, rails against regular hours, is sociable to a fault. But it is an industry that seeks to shine a light in dark places and yet often fails to shine a light on itself.

We have both suffered severe mental distress related to our work. We have both had breakdowns as journalists. We have both survived with the support of family, friends and colleagues, and have gained skills which allow us to deal better with the bad days – of which there are still too many. Not least openness, and the insight that talking helps.

But we know there are others who are struggling, and who are silenced, and we are worried.

The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, the International Center for Journalists, along with the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, and the Dart Centre for Trauma and Journalism have all highlighted the high emotional toll on journalists in this year of global pandemic.

Journalists are exhausted by the impact of Covid-19, unable or unwilling to switch off from the biggest story of their lives, one which affects us all albeit in different ways.

The industry has been forced to reinvent decades of work practice in weeks. Journalists are working remotely or on new frontlines of an invisible danger, with a vast visible impact, often infiltrating their own homes. The boundaries blur between work and home lives, with extra pressures for people who are isolated or impacted by limited space, noise, or having to share it children, housemates, or extended families. No different to anyone else, yes. But this is a community so used to social connection, suddenly disconnected, and yet which has to be hyperconnected too.

“We have both experienced the soul numbing emptiness of depression, the sense of being in a different orbit from everyone else.”

There has been huge progress in the debate on mental health and the openness to discuss it publicly, and the UK media can take much of the credit for that. But as employers, is the industry walking the walk?

All too often journalists are still fearful an admission they are struggling will impact their reputations, worried that speaking out will cost them a promotion, their next deployment, that it will make them a liability of sorts. This year has thrown into sharp relief the emotional burden carried by journalists of colour, who are often among the most marginalised and under-represented.

The two of us have been relatively fortunate, and we have the platform to speak out to show others they are not alone, to help people practise the skills that are needed to modernise outdated structures of management that reinforce taboos.

We both know behaviour that might look like coping but is effectively unsustainable self-sabotage. We’ve both done it. Drunk too much. Worked too hard. Put work ahead of family.

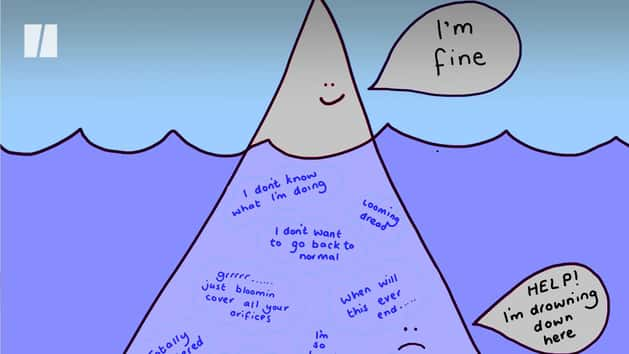

We have both experienced the soul numbing emptiness of depression, the sense of being in a different orbit from everyone else, and yet most of the time been able to put on our coping cloaks and get through the day. And we both know this is not healthy.

Journalism at its best is about the pursuit of truth. Owners and editors need to face up to the truth that right now, a lot of people are pretending to cope when they are not, pretending to be fine when they are not. It is the job of leaders to let those journalists know, it is OK not to be OK, OK to say so, and it won’t be held against them.

Hannah Storm is CEO and director of the Ethical Journalism Network. Alastair Campbell is a political consultant and commentator. Both will be in conversation at the IMPRESS Trust in Journalism Conference on November 23.